An interview on Yellow Springs News

Noted Japanese composer Keiko Fujiie will present “Wilderness Mute,” a multidisciplinary work of music, image, poetry and Japanese Butoh dance, on Friday, Sept. 21, 7:30 p.m., in the Foundry Theater at Antioch College. The work is in response to the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, and is slated in conjunction with an exhibit at the Herndon Gallery looking at nuclear bombing archival materials. Fujiie is photographed in the Antioch College president’s house. (Photo by Megan Bachman)

Performance, exhibit at Antioch — Bringing A-bomb history to light

- By Megan Bachman

- Published: September 27, 2018

When Japanese atomic-bomb survivor Kyoko Hayashi traveled to the Trinity site in New Mexico, where the first atomic bomb was tested 50 years prior, she found burned mountains, ruined fields, and a “wilderness forced into silence.”

As Hayashi recounts in her poetic text, “From Trinity to Trinity,” although she was a hibakusha, literally “explosion-affected person,” as a survivor of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945, she was moved to tears only after witnessing the bomb’s utter devastation of the natural world. She couldn’t even find an insect in the vast wasteland.

“Until now as I stand at the Trinity Site, I have thought it was we humans who were the first atomic bomb victims on Earth,” she wrote. “I was wrong. Here are my senior hibakusha. They are here but cannot cry or yell.”

“Wilderness Mute” by Japanese composer Keiko Fujiie derives its name from Hayashi’s empathetic encounter with the New Mexican desert. For Fujiie, a longtime resident of Nagasaki, the piece is inspired by survivors like Hayashi, who overcame their own suffering to connect with the suffering of others.

“She saw that Mother Earth was a victim before us,” Fujiie said of Hayashi. “It touched me so much.”

A collaborative, multidisciplinary work involving music, image, poetry and Japanese Butoh dance, “Wilderness Mute” is a response to the U.S. nuclear bombing of Nagasaki. The performance, only the second one in the U.S., will be held Friday, Sept. 21, 7:30 p.m., in the Foundry Theater at Antioch College.

The piece is in conjunction with “Nuclear Fallout: The Bomb in Three Archives,” with local artist Migiwa Orimo, which opens at Antioch’s Herndon Gallery the previous evening, Thursday, Sept. 20, at 7 p.m. with a talk by Orimo.

“Wilderness Mute” is a special performance funded by the Music of Remembrance, a Seattle, Wash., project that annually commissions compositions to remember the Holocaust. For its 20th anniversary year, the group commissioned two pieces on the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, selecting for one of them Fujiie, a noted and frequently performed Japanese composer.

Fujiie’s work draws from the firsthand accounts of victims of the Nagasaki bombing, unimaginable in its horror. She sees the accounts as vital to preserve.

“This atomic bombing is not possible to imagine, so before the last victim passes away, I have to share,” she said.

At the same time, Fujiie also wants her audience to see the universal nature of the problem and the present-day threat of nuclear proliferation and nuclear waste.

“We don’t want so many sentimental lamentations,” she said. “It is a tragedy,” she added of the Japanese bombings,

“but it is a tragedy everywhere.”

“We are all in the highest risk.”

In addition to the voices of the Nagasaki victims, Fujiie incorporates the poetry of Nobel laureate physicist-turned-peace activist Yukawa Hidecki. His poem deals with the mistakes made by early nuclear scientists such as himself, who, for their impressive achievements, unleashed a new terror on the world.

Through her piece, Fujiie hopes American audiences remember not only the human toll of the Japanese bombings, but also reflect on the 15,000 nuclear weapons currently stockpiled around the globe, “each more powerful than the ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” she said, and the legacy of nuclear waste contamination in their own country.

“Not only [those in] Japan are the victims, but in your own country so many people are suffering so much,” she said.

NAMU 南無 for Timpani, Japanese Drum and Children Choir

After the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear accident

A Vermilion Calm

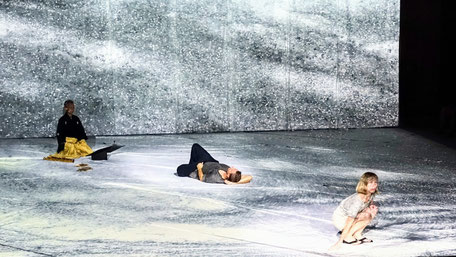

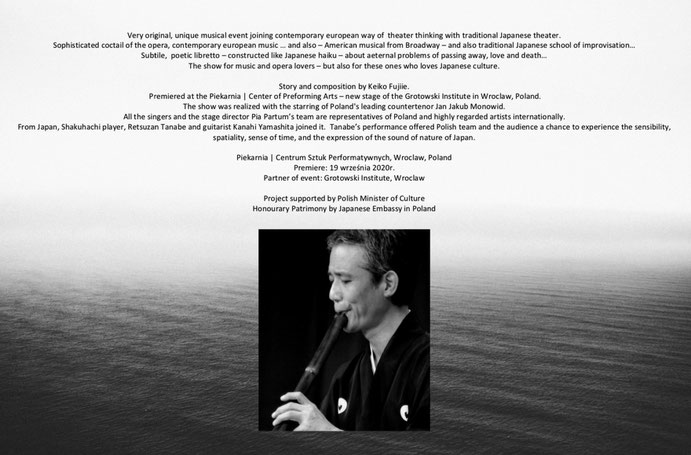

premiered in September 19th at Grotowski Institute, Wroclaw

©Keiko Fujiie (all rights reserved)